The debt limit – commonly called the debt ceiling – is the maximum amount of debt that the Department of the Treasury can issue to the public or to other federal agencies. The amount is set by law and has increased over the years to allow for additional borrowing needed to pay government obligations including Social Security, Medicare benefits, salaries, interest on debt, and tax refunds. Since 1960, Congress has raised or extended the debt ceiling 78 times. This has occurred during both Republican and Democrat Congresses/administrations. Many of the debt ceiling changes have been agreed in conjunction with major fiscal legislation used as a negotiation tool.

The U.S. is one of only two countries with a debt ceiling that is an absolute amount as opposed to a percentage of GDP. It appears Congress prefers the current method to approving debt levels in order to force both sides to the negotiating table on a recurring basis.

The decision to increase the nation’s debt limit is often a routine one; however, this time the scene is set for what could be one of the most contentious debt ceiling debates in recent history. Democrats have said they do not intend to negotiate on the issue, while many Republicans have said they won’t vote to lift the debt limit without additional agreements to cuts in spending. “This could be the worst standoff we’ve ever witnessed,” says Capital Group political economist Matt Miller.

Technically, the debt ceiling is about spending that has already occurred or been approved. Raising the debt limit would allow the Treasury to pay for spending that has already happened. This fact supports the argument the debt limit vote should be a stand-alone decision and not tied to a budget deal relating to future spending. The other side of the argument is that if the government does not address the serious increase in the level of debt now, then what other catalyst would ensure both parties come together on a budget deal?

In January 2023, the current debt limit of $31.4 trillion was reached, and the Treasury announced a “debt issuance suspension period” during which, under current law, it can take well-established “extraordinary measures” to borrow additional funds for a limited time without breaching the debt ceiling. A report issued by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in February 2023 projected the government’s ability to borrow using extraordinary measures will be exhausted between July and September 2023 – the exact timing will depend on revenue collections and outlays over the next several months. A big unknown is the amount of income tax receipts in April that could be more or less than the CBO’s projections depending on the estimated capital gains realizations in 2022 and U.S. income growth.

The CBO’s projected time frame was cut short this week by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in a letter to lawmakers. Secretary Yellen stated the agency may be “unable to continue to satisfy all of the government’s obligations by early June, potentially as early as June 1” and urged Congress to take action. Yellen cautioned the projection is imprecise and tax receipts have come in lower than anticipated in recent months.

The current situation has been compared to the debt ceiling showdown in 2011 that resulted in the credit rating agency S&P downgrading the credit ranking on U.S. debt for the first time in history. According to S&P Global Ratings, the rating agency is monitoring developments regarding the U.S. debt ceiling and its sovereign credit rating on the U.S. remains at AA+/Stable (one rating below the highest of AAA). The rating agency expects Congress will engage in brinkmanship with the debt ceiling but will ultimately address it on time, either raising it or suspending it, understanding the severe consequences on financial markets and the global economy if they do not act.

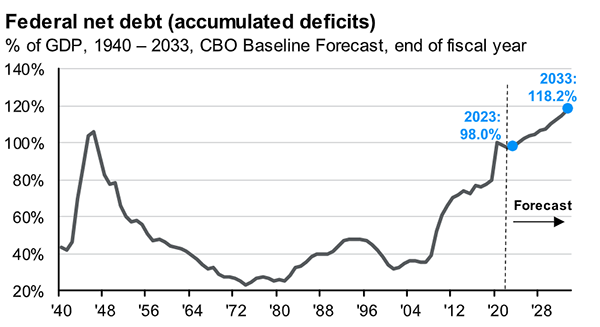

As mentioned, certain members of Congress want to tie the debt ceiling vote to a balanced budget deal, adding to the current tensions in Washington. Whether you agree with this negotiating strategy or not, the budget deficit and growth in debt warrant serious concern. As you can see in the chart below, U.S. debt to GDP has increased at a rapid rate and is projected to continue on an unsustainable path.

Federal debt is projected to rise from 98 %of GDP in 2023 to 118 % in 2033. Over that period, the growth in interest costs and mandatory spending outpaces the growth of revenues and the economy, driving up debt.

In 2022, the federal government spent $6.3 trillion and collected $4.9 trillion in revenue, resulting in a deficit. The budget deficit last year was more than $1 trillion for the third year in a row. The accumulation of budget deficits over the past several decades have resulted in the national debt of $31 trillion, well higher than annual GDP.

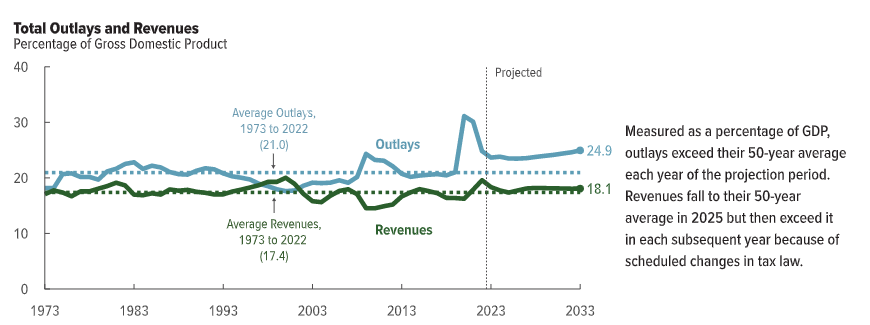

According to this graph, over the next ten years, outlays (spending) as a percentage of GDP will exceed their 50-year average annually, creating a wide gap over expected revenues. Budget deficits are projected for each of the next 10 years, pushing the national debt level even higher. With the expiration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, tax receipts will increase slightly starting in 2026; however, this increase in revenue does not come close to matching the increase in the level of outlays. This level of spending is not on a sustainable path and illustrates the need, if not now then soon, of balancing the budget.

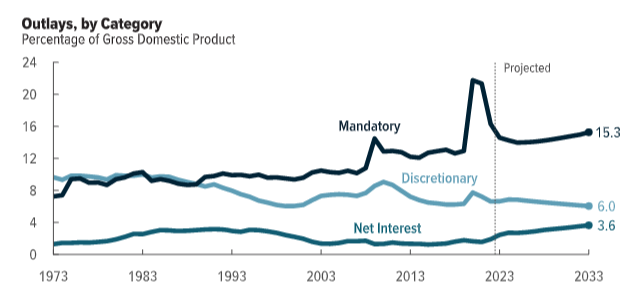

Two areas creating additional pressures on spending include the rise in health care costs and the increase in interest expense on the national debt given higher interest rates. The aging of the population causes the number of beneficiaries of Social Security and Medicare to grow faster than the overall population and federal health care costs continue to rise faster than GDP per person. Measured as a percentage of GDP (or put into terms of how this expense might be paid), outlays for Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other health care programs are expected to increase from 10% of GDP today to over 15% of GDP over the next 30 years. This segment represents the largest component of mandatory spending as shown on the Outlays by Category Chart.

The other rising, and more recent, problem is interest paid on the debt. Net interest costs are projected to double over the next decade from 2% of GDP in 2023 to 4% in 2033 – the highest level in any year since at least 1940, when data was first reported. This trend is expected to continue, driven by rising interest rates and growing deficits, with interest expenses doubling from 2033 to 2053, increasing from 4% of GDP to 8%. It appears that the era of “cheap” money and low interest rates that benefited the economy and the government’s debt management has come to an end.

Given that the current banking environment is expected to create tighter lending standards for individuals and businesses, the critical question is what could possibly limit the amount of government borrowing? One indicator will be whether we are risking the “safety and soundness” and high credit rating assigned to U.S. sovereign debt. The continued global demand for U.S. Treasuries enables the government to continue running deficits and borrowing (a seemingly unlimited amount of funds). Based on reports from the various rating agencies today it does not appear like we will see any changes in credit rating implications at this point, however, this remains a possibility. As a result of the current political dynamics in Congress, we anticipate that there is likely to be a protracted debate before the issue is resolved.

While we expect great deal of political maneuvering and headlines leading up to the debt ceiling debate in the coming months, we think an actual default on debt payments is unlikely. The issue will be resolved with the ultimate outcome being a higher debt limit, but the path taken, and the time involved is unknown. If a technical default did occur should a bond payment be missed or even delayed, it’s hard to predict what might happen next. A default would likely roil the financial markets, possibly create permanently higher borrowing costs for the U.S. government, and even jeopardize the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.

A more likely outcome is a last-minute budget deal that includes either caps on discretionary spending for future years, some sort of committee that can make proposals to reform mandatory spending programs, or both, as part of a bipartisan deal to raise the debt ceiling. In the highly unlikely path that the debt limit is not increased on time, the Treasury Department would still have sufficient cash flow to pay all securitized debt as it came due, as well as entitlements such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. To ensure that these higher priority payments are made, other programs and agencies would have to make significant cutbacks, which would be painful but do not a represent a default on the debt.

As we enter the summer months, we will continue to monitor any developments toward a resolution and are happy to address any questions or concerns you may have.

Unless stated otherwise, any estimates or projections (including performance and risk) given in this presentation are intended to be forward-looking statements. Such estimates are subject to actual known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those projected. The securities described within this presentation do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended for client accounts. The reader should not assume that an investment in such securities was or will be profitable. Past performance does not indicate future results.

Back to Insights

Back to Insights